When does an intense love begin to turn sour? At which point along the road do both sides realise they are better off without one another? When does the bad start to outweigh the good?

The story between Diego Maradona and Napoli is a perfect encapsulation of this, a once intoxicating romance that over time becomes insufferable, but when was the tipping point? Many believe that it came minutes after winning the 1989 UEFA Cup when, after being promised by club owner Corrado Ferlaino that he could leave for Marseille that summer should he bring home Napoli’s first major European trophy, Ferlaino gently whispered in his ear on the pitch at the Neckarstadion in Stuttgart that he was going nowhere, that in fact he had dangled the Marseille carrot as a means of motivating Maradona. “I wanted to smash the cup over his head,” wrote Maradona in his 2000 autobiography.

Others have pointed to the infamous tirade on the eve of the Italia ’90 semi final against Italy about the northern/southern divide. Whilst Machiavellian in timing, Maradona’s rant was generally a fair reflection on the way in which many Italians – then and now – view Neapolitans. It cut a little too close to the bone to many within the Italian Football Federation, and Maradona always believed that this, and Argentina’s subsequent win over Italy, was the death knell for his career at Napoli.

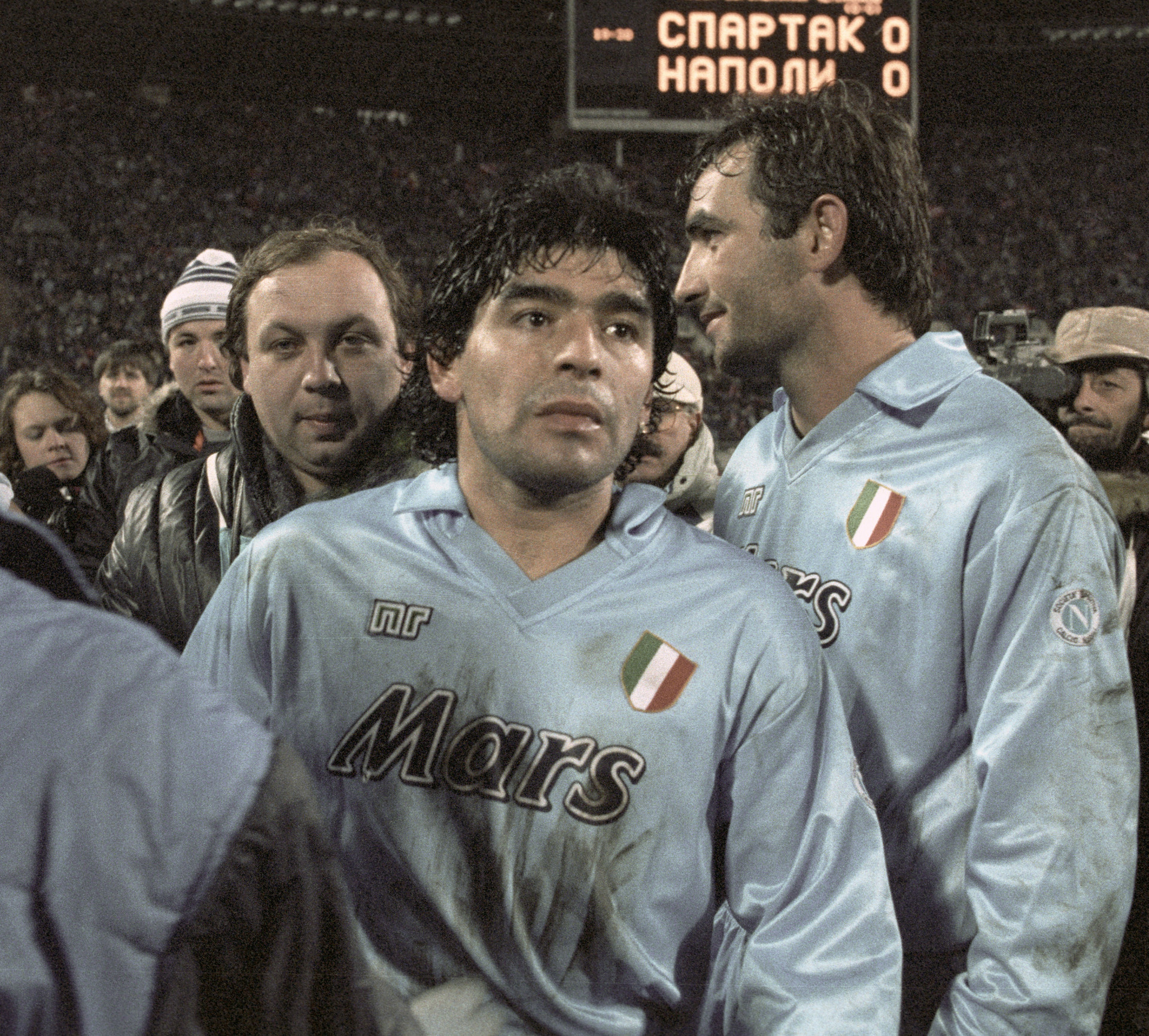

But the real beginning of the end came in November 1990, when Napoli were due to face Spartak Moscow in the second round of the European Cup. Napoli had breezed past Hungarian outfit Újpesti Dózsa in the first round, winning 5-0 on aggregate, with Maradona scoring twice in the 3-0 first leg.

This set up a second round tie with the Russian champions amidst the slow dissolution of the Soviet Union.

The first game, at the Stadio San Paolo, somehow ended goalless, with Napoli hitting the woodwork three times. Maradona was at his very best, with arguably his final great performance for Napoli. It was in the build up to the second leg that changed everything.

Napoli were due to fly out to Moscow two days before the Wednesday game. Everyone was present, except Maradona. This had become standard practice in the latter years, where he would arrive right at the last. “The club tried to reassure us that Diego would come,” wrote Ciro Ferrara in his book, Ho Visto Diego (I have seen Diego) about that Napoli era. “’He will arrive tonight to eat with us’. Then it became ‘he will be there tomorrow for lunch’. Then, with our tickets to Moscow in our pockets, they said ‘Diego is coming to the airport!’ but he didn’t.”

Ferrara then bandied together a group of players who decided to take matters into their own hands. They went to Maradona’s house in Posillipo to convince him to play. However they weren’t greeted at the door by their captain, but by his then-wife Claudia Villafane. Villafane, who according to Ferrara was visibly upset, said: “boys, Diego isn’t going this time.” Maradona was sleeping off yet another night of hedonistic debauchery, and Ferrara and Napoli departed for Moscow without him.

After eventually awakening from his slumber and perhaps being hit with a moment of sobriety, Maradona regretted his decision not to heed his teammates’ call. For all of his rebelliousness, self-destruction and contempt for authority, Maradona was always a players’ player, ready to go to battle alongside his teammates. This was evident in the hours and days after his death, when former teammates spoke of despite Maradona knowing who he was and possessing arguably the most innate talent any footballer has ever had, he never thought of himself as superior inside the locker room. He treated everyone as equals.

With the last pangs of cocaine and alcohol leaving his system and guilt the overriding emotion, Maradona booked a private jet at his own expense and flew to Moscow, arriving late on Tuesday evening. In fact, Maradona arrived so late that the hotel where he was staying had closed their kitchen for the night. This didn’t impress Maradona.

Aptly dressed for the Russian winter by sporting a long, garish fur coat, Maradona decided to get over his disappointment by visiting Red Square at two in the morning. Accompanied by Russian police, a problem arose when it was put to him that it was closed off due to the next day’s October Revolution anniversary celebrations, with a parade set to take place.

Maradona, being well, Maradona, wasn’t used to hearing no and wasn’t to be denied. He cajoled the guards at Red Square to break the highest levels of Soviet protocol and allow him in. He was given a guided tour of the square, and visited Lenin’s Mausoleum.

It’s easy to forget that this was the world’s greatest footballer, due to play in a European Cup second leg match in 12 hours’ time, and not some rockstar suffering from insomnia and thus killing a few hours in the middle of the night.

Spartak Moscow were no competition fodder, neither. This was still in the era when the Iron Curtain – just about – held the ‘crack’ Eastern European teams together, with most players unable to leave for the west until they reached their late 20s. Spartak had talented players like Igor Shalimov, Aleksandr Mostovoi and Valeri Karpin, who would all make the trek westwards after the fall of communism.

A crowd of 86,000 people inside the brutalist Lenin (now Luzhniki) Stadium witnessed a largely insipid game. The big news was that Napoli’s diminutive No.10 wasn’t Maradona, but Gianfranco Zola. Napoli had had enough of Maradona, and had warned him that if he didn’t arrive with the squad to Moscow, he’d be dropped, and they kept their word.

In the 63rd minute, Maradona was summoned off the bench by Alberto Bigon to try and secure victory. The game’s greatest No.10 now had the indignity of wearing the No.16. Napoli hit the post through Massimo Crippa after Maradona’s introduction, but he couldn’t stop the game from going to penalties.

Spartak scored each of their penalties. Maradona scored his, as did Ferrara and Massimo Mauro. Defender Marco Baroni didn’t, however, dragging his shot wide. The home side were through, and Napoli out. Maradona only played in the European Cup six times, and he’d never play in European competition again.

The early exit infuriated Napoli, costing them millions and a quarter final clash against Real Madrid. Ferlaino and sporting director Luciano Moggi – that bastion of sporting integrity – decided that Maradona’s volatile behaviour could no longer be tolerated, his performances could no longer justify it. They couldn’t sell him for fear of a lynching from Neapolitans, but they were no longer willing to protect him, with Moggi having to procure clean urine so Maradona would pass drug tests with increasing regularity. Maradona’s vices were Serie A’s worst-kept secret and, ostensibly, they were going to allow Maradona to hang himself.

Even Ferrara, who still idolises Maradona, believes Moscow was the beginning of the end. The haunting scene at the 1990 Napoli Christmas party, captured in Asif Kapadia’s 2019 documentary, shows Maradona – despite a room full of people – in a thousand-yard stare. The loneliness was stark; the spark well and truly diminished; a relationship in its dying embers.

The end came sooner than most expected. With Maradona now stripped of his invincibility from the club, stories circulated in the newspapers of his association with the Camorra. In February 1991 an investigation into a sex and drugs ring ran by the Camorra in Naples unearthed Maradona’s voice on wiretaps, which were subsequently leaked to newspapers.

And then finally, he failed a drugs test after the match against Bari on 17th March 1991, with his final game for the club coming a week later in a 4-1 loss away to champions elect Sampdoria, in which he scored his final goal from the penalty spot.

Spartak reached the semi final of the European Cup, beating Real before eventually losing to Chris Waddle’s Marseille. Maradona was banned for 15 months, his reputation in tatters at the age of 30. Napoli meanwhile finished 8th in Serie A, and have never won the Scudetto since. A glorious era had the most inglorious of endings, but neither Napoli nor Maradona were ever quite the same without each other. For all of its flaws, the most intense of player/club relationships was perfect, at least for a time.

But a trip to Moscow changed everything.